John Wyatt Greenlee and Anna Fore Waymack

About: This talk was delivered October 11, 2019 at Stanford University’s Rumsey Map Center, as part of the 2019 Barry Lawrence Ruderman Conference on Cartography: Gender, Sexuality, and Cartography. As this was a conference presentation, we have not included citations. We have left in speaker cues.

For related work, see our recent article “Thinking Globally: Mandeville, Memory, and Mappaemundi” in The Medieval Globe, our outline of the book project Insider Information: The Worlds of Medieval Identities, and Greenlee’s Mapping MandevilleProject, winner of the Medieval Academy of America’s 2019 Digital Humanities and Multimedia Studies Prize.

As always, both authors contributed equally, each more than the other.

Keywords: Christine de Pizan; maps; medieval; mnemonics; memory; gendered mapping

Anna

So. We’re going to be talking about how many medieval people used maps as mnemonic devices, and how at the start of the 1400s Christine de Pizan played with these mental maps. But before we get to that, let’s get everyone on the same page about medieval memory and maps.

Temple of Time, Emma Willard, 1846

Imagine growing up shaping your mind into a memory palace, using imagined physical spaces to hold thoughts, memories, and especially images; we are good at remembering images. Now, you want it structured sensibly so you can locate those pictures and ideas when you need them. You might organize it as a physical building, like this Great Man of History “Temple of Time” by Emma Willard that Susan Schulten showed us yesterday—we swear we did not coordinate this!— which is organized by people, places, centuries, and more. The palace itself provides the structure: columns and floor tiles to organize topics, for instance.

But, you don’t have to use a literal palace to hold your thoughts. Any overarching structure of places into which you can add vivid images to cue your memory about authors, quotes, trivia, or anything else, will do. This is how medieval Europeans, living in a memorial rather than literary culture, organized their minds. Memory, for them, needed an imagined physical place.

So to remember something you would visualize placing it in a location: literally, in loci or sedes, places or seats. These loci acted as mnemonic placeholders, and as you acquire pieces of information throughout your life you attach them to the physical spaces in your memory. You’re supposed to create your own unique memory palace.

But what if, like me, coming up with pictures is not your strong suit? You could use one that someone’s already made! Now, strictly speaking, you weren’t supposed to. Surviving elite medieval texts on memory look down on using a pre-fab mind. But we know that people did. And we know that they sometimes used maps of the world as a ready mnemonic framework for this purpose.

John Wyatt

This is the Ebstorf map, a medieval mappamundi, or map of the world, from the 13th century. It was enormous; almost 12 ft. by 12 ft, and it took 30 goatskins to make. Sadly it was destroyed in WWII, but prior to that Konrad Miller made this reproduction. To situate us…we’re looking down at the globe of the world from above — Europe is at your bottom left, Africa is on your right, the Mediterranean between them, Asia above. This is, clearly, not a map to navigate with (even if you could manage to fold it up and put it in your pocket)…that’s not its purpose.

Monialium Ebstorfensium mappa mundi. 1989 Reproduction by Konrad Miller. David Rumsey Map Center.

Mappaemundi are story-maps that lay out a Christian-centered history of the world, sometimes from Creation all the way to the Second Coming. Geographic distortions are of no consequence: the medieval mappamundi have to contain multitudes of stories, represented in text and in symbols, and these are more important than the ratios of geography.

This map goes so far as to show the entire world, past and present, as the body of Christ. You can see his head at the top, and at the edges of the world are his feet and hands with their stigmata. The history that unfolds on this terrestrial Christ reads from top to bottom, running from Paradise to Babylon to Jerusalem, at roughly the center of the world, to Rome.

Amazons on the map. (1898 reproduction)

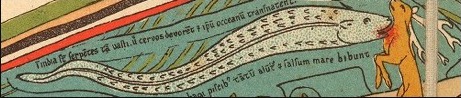

The map includes a range of marvelous creatures, peoples and events. Some were drawn from the Bible, such as the image of Bethlehem with its star, or from Classical mythology like the Amazons, or natural history with the image of this giant, deer-eating serpent from India. And it includes numerous monstrous humanoid peoples, mostly at the edges of the world.

A giant fish eating a deer. (1898 reproduction)

Each of these images offers a place to set your memories. The more marvelous or grotesque the better; it makes them easier to remember. But you don’t simply use the map to remember these stories or events. These images, with their familiar but wondrous natures, serve as mnemonics for other memories. We might, for example, use that image of the Amazons as a locus for remembering details about an online purchase we want to make. The vivid images on the map become the loci for storage, with the world itself as the memory palace.

We’ve argued elsewhere that this was a widespread practice: that maps circulated in medieval Europe for the purpose of templates. But…that we’ve missed a lot of them—because they’re textual maps.

Anna

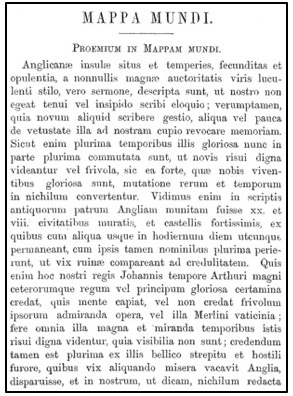

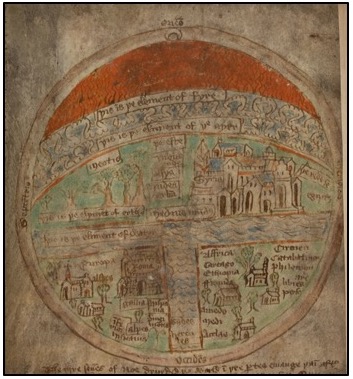

This, believe it or not, is a map. Look, it tells you! It’s a map of the world that Gervase of Canterbury, a late 12th century monk, included in his chronicle. It’s a prose map, and that was a thing. Think about these as a step further than the word maps of Connecticut and Vermont Susan Schulten showed us yesterday. Many self-identified maps offer up the world as lists of cities or provinces, sometimes arranged in a geographical schema, as on the neglected verso of the popularly-cited thirteenth-century Psalter map.

Mappa Mundi, c. 1200, Gervase of Canterbury.

Medieval chronicles frequently include some kind of map – a fact that modern readers often miss because we usually only think about maps as images. Ranulf Higden labels the whole first book of his fourteenth-century Polychronicon the Mappamundi. Gervase of Tilbury’s 13th-century encyclopedia, the Otia Imperialia — which is possibly connected to the Ebstorf Map — includes a book that describes all the world and its wonders. In the 1200s Matthew Paris included both textual and visual maps at the start of his history of Britain, and in the century before that historians such as William of Malmesbury or Henry of Huntingdon also began their works with descriptive textual geographies.

These historians are looking back to Bede, who began his 8th-century Historia Ecclesiastica by describing Britain, giving its dimensions and carefully placing the coastline, cities, and islands — providing space to help remember the history to come. Bede, and the chroniclers who followed him, offered a map to aid their readers.

Mandeville Setting off on his Journey BL Additional 24189, f.3v.

These sorts of textual maps were not only found in chronicles.. Other types of texts also provide us with maps, and one of the best examples being the 14th century Travels of Sir John Mandeville…a fictionalized account of a fictional knight’s journey from England to Jerusalem and onwards, detailing the routes and sights along the way. The Travels was hugely popular. We have more than three hundred surviving manuscript copies, double that of Marco Polo, and they belonged to a wide range of readers. The Travels was translated again and again, adapted into poetry and into pictures, and, in short, was the Harry Potter of its day. It is, though, a text that defies easy categorization. It’s not a chronicle, exactly, or a romance, though it has elements of both. What it does offer, however, is a description of the world.

John Wyatt

This is a mappamundi that prefaces one of the many manuscript copies of The Travels, but it is in many ways redundant, because the text of The Travels itself reproduces and fills in this world. Many of the Travels’ vignettes, such as the descriptions of monstrous races or natural wonders, match the materials found on the visual maps. Likewise, the spiritual and moral geographies that mark the mappaemundi as part of an identifiable genre find their way into the Travels.

Mappamundi from The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, c.1500. BL Add MS 37049 f. 2v.

On multiple occasions, Mandeville tells his audience that Jerusalem sits in the center of the world and describes the important sites of the Holy Land. He places a terrestrial Paradise in the uttermost East, and writes about the four major rivers that flow from Eden out into the world. Verbally, the author fills his world with the same content that gives flesh to the bones of the visual maps, describing these elements in vibrant terms that render them visible to the mind. On top of this he layers a description of routes of travel, connecting wonder to wonder. And the author notes in his prologue that he welcomes readers to add to his map from their own experiences, as his own memory does not contain, or retain, everything.

So what Mandeville’s text gives you is a map, prefabricated, that you can carry around in your head. You’ve got all sorts of images and details populating it in clusters that you can use as mnemonic containers. You’ve got paths structuring and connecting these loci. And you’ve got an invitation from the author himself to “amend and correct” your map. It’s customizable to you.

Anna

Now, the idea of using the earth itself as a storehouse for memory is an ancient one. Augustine of Hippo describes his own memory as the world in microcosm, an almost tangible place where he can visit fields, mansions, and caverns of memory with all manner of stored images. He says even the “sky and earth and sea are readily available” to him and that the “measureless plains and vaults and caves of my memory,” are “immeasurably full of countless kinds of things which are there either through their images…”

Augustine of Hippo. 1480, Botticelli.

In addition, he says that memory “is the mind, and this is nothing other than my very self.“ Augustine advances and popularizes the notion that he is his memory, conceives of himself as his mnemonic device: the shape of his memory, his mental world, is his own self-image. And so the pre-made, customizable world that Mandeville provides is not only a memory aid; it is offering readers a pre-made self.

John Wyatt

But it is a map, and a mind, and a self, which is highly gendered. The mappamundi of John Mandeville offers a world of, and for, men. Women generally only find mention in Mandeville’s text where they are monstrous or unsettling: a race of women with deadly snakes hidden inside their vaginas; a princess turned into a terrifying dragon; the Amazons who upset the natural social order; Eve in the Garden; and so on. This is a world of male stories and histories that can be figured as the literal, male body of Christ. It’s a handy template —if you’re a dude.

Anna

Not all of us are dudes.

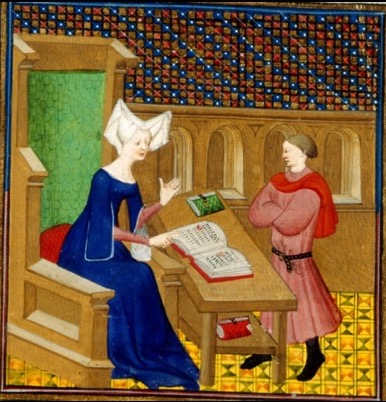

Christine and her son. BL Harley 4431 261v.

One woman for whom this mapped self did not work was Christine de Pizan. Regarded as one of the first feminists, Christine wrote in France at the turn of the fifteenth-century, at the height of Mandeville’s popularity. An author and poet of great scope, Christine began writing midlife as a widow, covering politics, love and morality. Her patrons included the Duke of Orleans and the Duke of Burgundy; she dedicated books to kings and queens. She is perhaps most famous for her long poetic work The Book of the City of Ladies. Despite these literary successes, Christine struggled to reconcile this broadly available male memory-world with her own experiences and abilities, trying to work through the implications for her personal knowledge and identity.

Cadmus and Io. BL Harley 4431 f. 109r.

We can see evidence of this. In the painting here from one of her early works—from a manuscript she probably supervised—she’s written about Cadmus as the founder of a school and shows him at founding of Thebes, a tale in which he causes men (and only men) to spring out of the ground. Yet she’s juxtaposed it with an image of Io in a scriptorium.

In classical mythology, Io was one of Zeus’s mortal lovers, and he turned her into a cow to hide her from Hera. Christine offers a very different version of Io’s story, skipping all that and telling us that she was the inventor of “many manners of letters of the alphabet.” Christine further adapts the myth of Io to add an analogy: “She became a cow, for just as the cow gives milk, which is sweet and nourishing, she gave, through the letters which she invented, sweet nourishment to understanding.” (62-3) Christine has repurposed the story to focus on the woman’s contributions and achievements, rather than her suffering. But the image also shows Io being silenced; we see Io as the sole woman, dispensing letters to the men but not, herself, writing. The land here is covered by—producing, even—only men, reproduced by an apparatus that’s credited to a woman but only wielded—even in this picture!—by men.

John Wyatt

This evidently didn’t sit well with Christine. In 1402 she tried to work through this disjunction in her poem, The Book of the Path of Long Study. The poem begins with the author-narrator reading Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy before falling asleep in her library and then waking in a dream-state to meet a guide, the Sibyl. In her vision, the Sibyl accompanies Christine through a now-familiar landscape: it’s the memory-world as unmistakably described by John Mandeville. She’s not using an image she’s created from scratch: she’s working with a commonly-available, prefabricated mental model.

The Fountain of the Muses on Mt. Parnasus. BL Harley 4431 f. 183r.

The Sibyl takes Christine down the Path of Long Study throughout her remembered world, bringing her to the Fountain of the Muses on Mt. Parnassus. The Sibyl implies that the great scholars and philosophers of the past, from Socrates and Plato to Galen and Avicenna, each frequented this fountain, and are now part of the nearby landscape. Routes that Christine imagines those scholars wandering in their own day branch out from the fountain, and Christine’s Path of Long Study is among them. These paths criss-cross the map of the world, leading to information on flora, fauna, peoples, and concepts, and as the Sybil guides Christine along she is able to gather up the knowledge necessary for thought and composition.

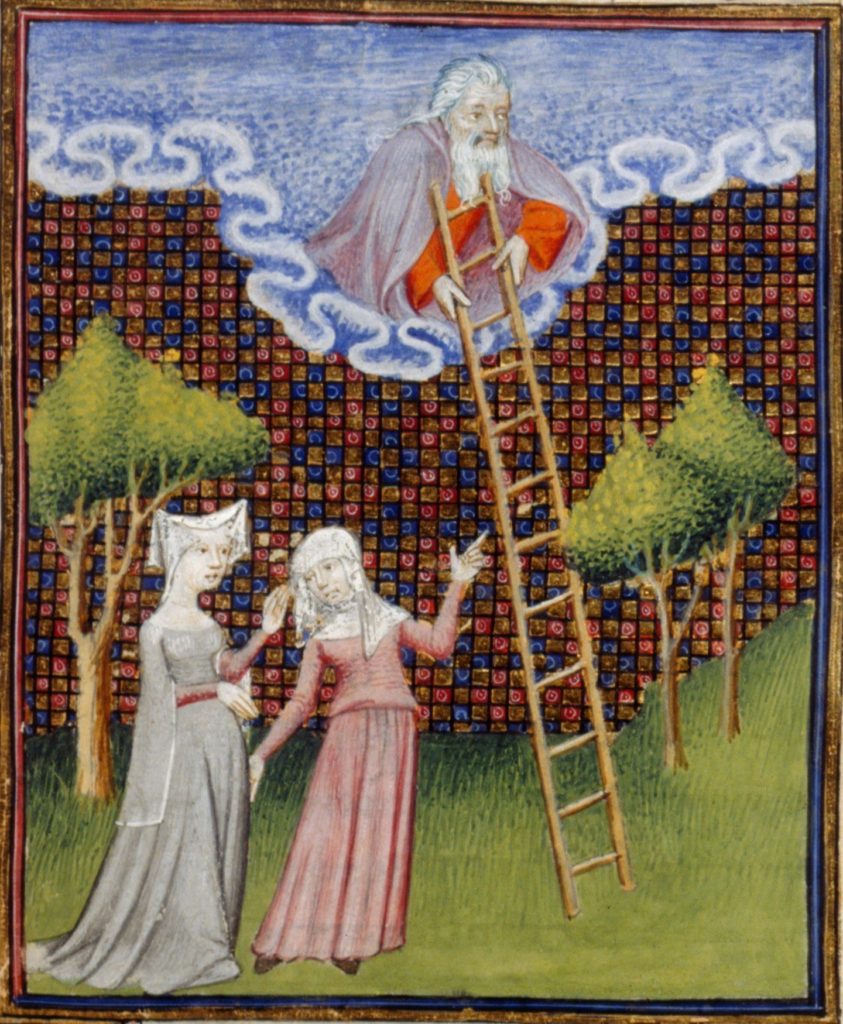

Christine and the Sibyl ascend to heaven. BL Harley 4431 f. 188r.

The Sibyl leads Christine on from the Fountain, taking her on a tour of the world. They pass through the lands, and see the things, described by Mandeville, before coming eventually to the gates of Eden in the furthest East. This was the limit of Mandeville’s described world…the point at which his fictional knight had to turn back. But Christine and the Sibyl press onward. They cannot enter Paradise but they climb its mountain, and from there ascend via a ladder to the heavens, leaving the memory palace of the world behind.

Anna

The Sibyl takes Christine up to the cosmos to mull over her material. Here, the poem shifts from the language of learning and knowledge to Christine’s active thinking; she describes herself in contemplation, attempting to understand, observing, concentrating, regarding, and other such acts of cognition.

Considering the Cosmos. BL Harley 4431 f. 189v.

In this place of imagination, she listens as Lady Reason holds court. Finally, Reason sends Christine back to earth to report on the debates she has heard, reassured by Christine that nothing will be left out because she has written everything down. Christine thereby reveals that she’s been describing the process of writing this very poem, using the assembled knowledge from the memory-journey.

The Court of Reason. BL Harley 4431 f. 196v.

So we’ve got a snapshot of the conflict that Christine is working through. The mnemonic map that she has to use to access her memories is male — she’s inherited it from her father, it’s clearly derived from Mandeville’s, and it’s both constructed and populated by men. But her means of accessing it is female: the Sibyl. And Christine has to leave the world, and ascend to a vantage point in the heavens, before she can think clearly in the all-female Court of Reason. To get there she has had to go all the way back to the gates of Eden — back to the start of history, almost undoing it as she travels — to try to find herself. There is an effort here to reconcile her rational female self with the mapped male self of her memory by emphasizing how the critical apparatus of thought has always been personified female. It’s still not enough.

John Wyatt

And it was not enough because the mind, with its memories is the self, and Christine could not bring herself to be comfortable in an identity constructed of men. Partly this was because she doubted her own rights to the territories of knowledge that had been her father’s. She writes about wanting to inherit his fantastic treasure: she says that he “had plenty of precious stones, very noble and powerful, that he took from the fountain” of the Muses—the same one she referenced earlier. To be clear, Christine’s father absolutely did not leave her an earthly fortune when he died. He was a well-known scholar and intellectual, but then…as now…that does not generally lead to wealth. His gems were astronomy, medicine and other pieces of learning.

Christine lays out her claim to this inheritance based on her strengths — the qualifications that Nature has given her. In a striking metaphor Christine describes herself as having a magnificent jeweled headdress with four main gems, that represent Retentiveness, Memory, Discretion, and Consideration. The most important are Retentiveness and Memory. Retentiveness, which she says “cannot be praised too highly,” covers everything that she personally experiences, senses, and feels, including emotions. The matching gem of Memory is for what we might think of now as book learning, or secondhand knowledge: things she’s heard about or read. Jointly, the gems in this crown rule the body “like an empire or a kingdom,” she says, “or even the entire world, for as long as [the globe] endures.” Christine, it’s worth noting, is the globe here. But even though these gems of personal quality are hers, the wealth of knowledge and learning remained locked in a mnemonic world that her father meant for a male heir. Although in every other way she’s an ideal successor, she’s female, and she writes angrily, “More by custom than by right, I could not inherit the wealth that was taken at the esteemed fountain.”

In Path of Long Study, Christine experimented with regendering access to the map. Within a year she tests out another approach: in the 1403 Book of Fortune’s Changes she tries making her own bodily sex the variable. She wrote in Fortune’s Change about her experiences after the death of her husband and father, when she had needed to take on the roles of provider and head of household previously managed by the men around her. In her real life she needed to become, as she saw it, functionally male. In the poem she describes her character as literally becoming a man, writing that Fortune has physically transformed her. And it is only at this point, writing and thinking as a man, that the Christine-narrator feels able to utilize her father’s inheritance in full. But as she navigates what she presents as as absolute binary, she is unhappy with this outcome, even though it has allowed her access to the memory-scape that she yearned after. She tells us that “It would please me considerably more to be a woman, as I was used to being.” She has still not been able to resolve the conflict between her natural self and the imposed self of a male mnemonic geography.

Anna

Every time Christine shows us her thought processes, she merges memory, identity, and geography, making her mind this shared literary mappamundi, often enough to make it clear that this is how she saw her internal self. And every time, it presents a problem: it’s Mandeville’s. It’s her dad’s. It is made up of men, for men, and her attempts to balance that with a female apparatus or to alter her own gender to match the map don’t quite resolve: there’s an ongoing dissonance and even dysphoria.

Two years later, she begins her best-known work, City of Ladies, by finally articulating the problem: her experiences—held by her Retentiveness —are at odds with all she reads, the substance of her more formal Memory. She needs Memory and Retentiveness to function together as a single map, but at least one of them is giving her the wrong coordinates. And her specific problem has to do with gender. Everything she reads says female nature is “beset by vice.”

Christine is, frankly, lost: she measures what she reads, from “so many illustrious men,” against her own experiences, her self-knowledge, and her many female acquaintances. She’s stumped to the point of, as she describes it, a stupor: “regardless of how long I thought about it […] I could find no truth in their condemnation of women’s nature and moral character. Yet their opinion was hard to ignore, because it would be too bizarre if so many reputable men and venerable clerics of great intelligence and vision had been telling lies on so many occasions.” Her initial conclusion? She must be wrong, and therefore—since she can’t see how she’s wrong—she must be wrong because she is, as a woman, less intelligent. Her lived experience, since it’s filtered through her, makes for an unreliable map. The male authors embedded in her inherited mental territory claim to know her nature better than she herself can.

John Wyatt

The solution she comes to, in City of Ladies, is to build a new geography for thought, wisdom, and memory — one specifically gendered female. In the text Christine is approached by the personifications of Reason, Rectitude, and Justice, who tell her that she is wrong to doubt her abilities, her intellectual inheritance, and her lived experience. They inform her that she must build a new City of Ladies that will be constructed by, and for women.

Measuring and Building the City of Ladies. BL Harley 4431 f. 290r.

Each figure carries a tool to help in its construction: Reason a mirror so that Christine might clearly see herself as she truly is; Rectitude a ruler for measuring the walls and public places of the new city; and Justice holds a measuring cup which she says offers the true measure of all things, and which will apportion out the city’s lived spaces. And perhaps even more importantly, they say their tools are for measuring the world anew, for Christine must re-survey her mental spaces.

The three figures take Christine to the “Field of Letters” where she begins construction under their supervision. Christine excavates the ground by asking questions of Reason, such as why there are so many literary attacks on women, while Reason carries away the earth by answering. In the ditch they dig out they lay the foundation: Christine’s pen is her trowel, and Rectitude tells her to “mix the mortar in [her] ink bottle.” The first stones of the foundation, courtesy of Reason, are the individual stories of Queen Semiramis and various Amazons. We saw earlier with Cadmus’s city of men, at Thebes, that men sprang from the ground, Here, the dirt of men has to be excavated and these women must be re-entrenched — fixed — into the Field of Letters.

Next comes a defensive wall of intellectuals, including Sappho—who’s described as frequenting that same fountain of the muses near Mount Parnassus. Rectitude gives Christine beautiful stones for masonry—the stories of female prophets and so on, building houses, streets, squares, palaces and towers—and then places exemplary wives into those palaces. Justice adds the roofs.

Notice how much of this construction relies on Christine using her cognitive sense — her Reason — in spatial organization. Where in Path of Long Study Reason and her female court were only able to look down on the world from above, here Christine has brought Reason into direct interaction with the map, using her intellect as a physical tool to cut into the terrain. The gendered division between ground and heaven, memory and cognition, has collapsed.

Anna

There’s another curious dynamic in Christine’s process of remembering or learning about some of the women who make up the stones of the City. Up until now they’ve either been hard to find on her mental map—wandering, mislocated or obscured—or been entirely omitted. She describes Sappho as wandering: frequenting Parnassus, entering forests, going on her way to Apollo’s grotto and the fountain and brook of Castalia. In creating a foundational stone of Sappho’s history, Christine gives her precise coordinates for future access, cross-referenced with other female peers.

Shortly after that, Christine has to ask Reason whether “there was ever a woman who discovered hitherto unknown knowledge”—she (ostensibly) doesn’t know. And the very first of Reason’s responses demonstrates how appallingly the existing map fails women. Reason says a woman named Nicostrata or Carmentis invented the Latin “alphabet and syntax, spelling, the difference between vowels and consonants, as well as a complete introduction to the science of grammar.”

In short, Nicostrata—like Io earlier—provided the very means of accessing and transmitting the elements of these literary landscapes! In case we miss the significance, Christine returns much later to how “practically endless number of books and volumes” use Nicostrata’s script, holding history, theology, arts and sciences, the stuff of these maps, “in perpetual memory.” But even if Italians supposedly named things in her honor, including a gate of Rome, Nicostrata’s dropped off the maps Christine had available. Placing her in the same wall as Sappho shores them all up, defensively.

John Wyatt

And to be clear, Christine is not building a whole new mental world, but rather carving out this new space within a pre-formed terrain. The text places the Field of Letters within a wider world — it exists within the map that Christine had already been working with. But the text also stresses that this is not a friendly world; the City of Ladies needs walls and strong defenses because of the well-documented hostility of male writers.

Welcoming the Virgin and the Saints to the city. BL Harley 4431 f. 361r.

When the construction is complete, Justice invites in holy ladies, past and present. We can see here Christine and the three figures welcoming these women in at the gate. They come bearing books and relics of wisdom to add life to the newly built geography of their city.

But this is not simply a space for Christine and her own memories. She is clear in her writing that the city has space for women to come as well, and that the purpose of the city is to offer a haven for memory into the future. The mental map that Mandeville offered was a shared and communal space, living in texts and broadly available. Christine is hoping for the same — to craft a mental territory through her book that would last into the future, and that later generations of women might use to aid in memory and self-knowing.

Anna

What she’s built answers at least two of her specific conundrums. First, she has created a lasting means of seeing and measuring more accurately, checking her perception—and allowing other women to check theirs—within the bright reflections of their composite city. But second, she’s answered the inheritance of literary mind-maps: this city is, as Rectitude says, better than earthly ones. Legacy needn’t pass through bodies, and Christine doesn’t need to qualify as her father’s heir or birth her own. Instead, without relying on men’s contributions or approval, she can inherit the intellectual gems of past women. Future generations can inherit hers.